On this page

- 3.1 Introduction

- 3.2 Digital Equity Assets

- 3.3 Overview of Digital Equity Needs and Barriers

- 3.4 Specific Barriers and Baseline for Covered Populations and Digitally Disadvantaged Communities

- 3.5 Specific Barriers by Priority Outcome Area

- References

3.1 Introduction

As noted in the State’s Broadband for All Action Plan in 2020, the vast size and diversity of California makes broadband delivery a complex issue.[1] California’s diverse geography and topography pose immense challenges. Five percent of California’s population is spread across 147,000 square miles of the state, while the remaining 95% live in urban areas that span 8,200 square miles.[2] This geographic divide compounds the digital divide in California.[3]

There are regional and local differences in the amount of historic investment, lack of competition, and need for additional funding to incentivize broadband infrastructure expansion and adoption. This has led to disparate access and a persistent digital divide that impacts our most vulnerable communities and residents. This Plan is focused on alleviating digital equity barriers for members of covered populations who are most impacted by the digital divide.

Access

At the close of 2018, nearly 95% of the State’s households had access to broadband download speeds that were advertised at 100 Mbps or greater due to extensive deployment of cable and fiber infrastructure in densely populated urban areas.[4]

Using the NTIA and FCC’s broader eligibility criteria for served locations, California has an estimated 306,910 unserved locations (lacking 25/3 service) and an additional 151,107 underserved locations (lacking 100/20 service) based on FCC data.[5]

Affordability

According to data from CETF and California State University, Chico, 2.7 million (47%) of the 5.8 million eligible households are enrolled in the ACP.[6] Concurrent with the CPUC’s BEAD Five-Year Action Plan, this Plan found that while low-cost internet service offers and subsidies are available, there is low awareness of these programs.[7] Additional barriers include difficult enrollment processes, eligibility rules that don’t factor in California’s high cost of living, lack of culturally competent and accessible outreach, and general mistrust in government and corporations.[8]

Adoption

U.S. Census Bureau data indicates that about 8% of households in California lack a computer or broadband subscription. Further, about 19% of the State’s population does not use the internet, and around a third of the population does not use a tablet or computer.[9]

The statewide telephone survey and online public survey obtained granular data on Californians’ comfort level with device usage, digital literacy skills, and online privacy and cybersecurity. The telephone survey found that one-third of households that do not subscribe to the internet do so because nobody in the household has a desktop, laptop, or tablet, supporting the theory that device access impacts broadband connectivity.[10]

Seventy-one percent of respondents to the online public survey said they use a laptop, with 54% using a tablet and 40% using a desktop to connect to the internet. However, over 90% said they use a smartphone to connect to the internet, making it the most used device.[11]Per the NTIA’s Internet Use Survey, 34.8% of Californians do not use a desktop, laptop, or tablet.[12]

When asked about digital skills, 56% of respondents to the telephone survey self-identified as “high-skill” users.[13] Most respondents to the online public survey said they were comfortable with basic skills such as sending an email with an attachment (84%) or searching for a job online (84%).[14] However, a much lower percentage of respondents to the online public survey (57%) said they were comfortable with cybersecurity such as setting up protections against phishing and spam email. There is strong interest by respondents (33%) to take an internet or computer training course.[15]

Data

Data granularity and accuracy was cited as a barrier during the development of the Broadband for All Action Plan and remains a barrier today.[16] While significant efforts have been made at the state and federal levels to improve broadband availability, affordability, and adoption data, there are small but significant differences in what the data is saying and is heard from communities and residents based on their lived experiences.

For example, the data from NTIA and the FCC may indicate that 95% of the state has served levels, but according to the California Community Foundation, “19% of LA County households and 16% of California households remain unconnected or under-connected to the internet.”[17]Similar input has been shared throughout the planning process from other entities including the Fresno Coalition for Digital Inclusion,[18] and #OaklandUndivided.[19] Both statements may be true because of how the Federal and State programs define “served,” while “unconnected” could be due not only to lack of facilities, but also lack of affordability, or lack of a device.

Continuing to prioritize the accuracy of data at the location, household, and unit level is critical to understanding the true extent of the barriers and creating strategies to counteract those barriers. CDT and CPUC are committed to improving the state’s data collection methods and working with stakeholders at the State and local level.

3.2 Digital Equity Assets

California has a strong and increasingly mature digital equity ecosystem that has been growing since the creation of the CBC. While developing the Broadband for All Action Plan, the State expanded its awareness of State agencies, organizations, entities, programs, and funding sources that support digital equity efforts.

CDT and CPUC are coordinating the development of the State’s asset inventory through the concurrent SDEP and BEAD planning process. Because both efforts are designed to create one State asset inventory, CDT included most of the assets CPUC identified in the BEAD Five-Year Action Plan in this Plan’s asset inventory.

CDT also gained new insights into California’s digital equity landscape through a new Digital Equity Ecosystem Mapping (DEEM) effort. More than 400 community anchor institutions, government and public organizations, private sector and non-governmental organizations, Internet Service Providers, and tribal entities used new DEEM tools to “put themselves on the map,” sharing details about the digital inclusion programs, services, and assets they provide. The DEEM tools identified organizations, programs, resources, and gaps in California’s digital equity ecosystem and further informed the State’s asset inventory included in this Digital Equity Plan.

This section includes:

- An overview of organizations whose work is essential to achieving the State’s Broadband for All goals,

- A summary of DEEM respondents, and

- Key findings and gaps in existing efforts.

CDT acknowledges that this Plan is not inclusive of all the assets in the State. Given the state’s scale, it is difficult to accurately quantify where gaps in digital inclusion programs and services exist relative to needs. Nonetheless, the planning and engagement process that informed this Plan, including hundreds of meetings with organizations supporting digital inclusion activities and responses to DEEM tools, shaped CDT’s understanding of its role in strengthening this ecosystem statewide and for covered populations.

Overview of Organizational Assets

California has long engaged with a wide range of organizations throughout the state to promote digital equity. From the creation of the Broadband for All Action Plan through the development of this SDEP, these entities have consistently partnered with the State to ensure progress is being made toward digital equity. These entities include statutory bodies such as members of the CBC, State agencies for education, workforce and economic development, health and civic participation, nonprofits, community- based organizations, and local, regional, municipal, and tribal governments. A complete list of these entities can be found in Appendix C.

California Broadband Council Members, Action Item Plan Parties, and Key Partners

Members of the CBC, entities responsible for implementing various items in the Broadband for All Action Plan, and key partners all played significant roles in the digital equity planning process. Many of these entities are part of the Middle-Mile Broadband Initiative, Middle-Mile Advisory Committee, the digital equity Statewide Planning Group (SPG) and the Outcome Area Working Groups. These entities were critical to the development of the plan and will be highly engaged in its implementation. A complete list of these entities can be found in Appendix D.

Regional Broadband Consortia

The Regional Broadband Consortia support the deployment of broadband services in regional and local communities, including provide technical support for applicants to State programs in project development and application processes. Regional Broadband Consortia are supported by the CASF Rural and Urban Regional Broadband Consortia Account, administered by the CPUC, which has distributed $10 million to 15 regional consortia for work over the next three to five years.[20]

Regional Broadband Consortia have been critical participants throughout the outreach and implementation processes for Regional Planning Workshops, as well as disseminating both the telephone and online survey, and the DEEM tool to their respective networks. A complete list of the Regional Broadband Consortia and the Counties they represent can be found in Appendix E.

Statewide and Regional Partners

CDT collaborated closely with many statewide and regional partners in support of its digital equity planning efforts. Many of the following partners have collaborated with CDT since 2020 in support of the development of the Broadband for All Action Plan. These partners assisted in the implementation of Action Items and worked with CDT throughout the development of the SDEP. These partners were instrumental in a successful public engagement campaign, ensuring that voices community members and those with lived experience could participate in the process. A complete list of Statewide and Regional Partners can be found in Appendix F.

Local Digital Equity Coalitions

Local Digital Equity Coalitions play an important role in informing and engaging local communities on matters of digital equity. A resource guide was developed to assist local and regional governments in designing their own digital equity plans.[21] A list of Local Digital Equity Coalitions who partnered in this effort can be found in Appendix G. These organizations were included in outreach for all forums noted in Section 4 of this document and were also encouraged to invite their networks to participate as well.

State-Managed Assets for Access, Affordability, and Adoption[22]

The State of California currently manages a significant inventory of physical assets, grants, and public-facing informational resources in support of digital equity. The following assets are managed or administered by multiple State agencies but are all in support of digital equity. A list of State-Managed Assets for Access, Affordability, and Adoption can be found in Appendix G. This is a non-exhaustive list. CDT and CPUC are coordinating to have one asset inventory. Additional assets can be found in the California BEAD Five Year Action Plan from pages 45 – 63.

Digital Navigation Service Providers

Per Assembly Bill 2750 (Chapter 597, Statutes of 2022) CDT is required to include in the Digital Equity Plan, “An assessment of existing digital navigation programs in the state and recommendations for a statewide strategy for digital navigators to serve covered populations, including opportunities to integrate with other social service outreach programs and opportunities for covered populations to participate as navigators with training they can then leverage to enter careers in the information technology sector.”[23]A complete list of organizations who responded to the DEEM tool and self-identified as offering digital navigation services can be found in Appendix I.

Digital Equity Ecosystem Mapping (DEEM) Tool

CDT developed the DEEM tool to further build out the State’s existing asset inventory at a more granular regional and local level and to better understand the organizations and entities providing digital equity services in California. The DEEM tool has enabled CDT to expand its statewide inventory of entities, programs, and funding sources methodically. Most importantly, the DEEM tool identified where resource gaps exist. CDT intends to update the DEEM tool on a regular basis.

The DEEM tool was promoted through email campaigns with multiple distribution partners, via social media, direct outreach to organizations, and at State Digital Equity Planning engagement opportunities including quarterly Statewide Planning Group Meetings, Outcome Area Working Group Meetings and Regional Planning Workshops. Other partners in CDT’s ecosystem further promoted the DEEM tool among their constituents, including AARP, RCRC, CWA, SANDAG and CSL.

CDT created three versions of the DEEM tool to address the unique needs of government and community-based organizations, internet service providers, and tribal entities. The tool was distributed over six months, from February to August 2023, and garnered 466 responses. As of August 2023, the DEEM tool has reached over 1,400 organizations across the state. These organizations include educational institutions, community-based organizations, private companies, and government entities. A complete list of organizations that responded to the DEEM tool, their program(s), covered populations they serve, and funding sources can be found on the Broadband for All portal and attached as Appendix J.

Respondent Profiles

Respondents to the DEEM tool represent a broad array of organization types within California. The three organization types surveyed include community-anchor institutions, government and public organizations, and private sector and non-governmental organizations.

Additional Assets by Covered Population

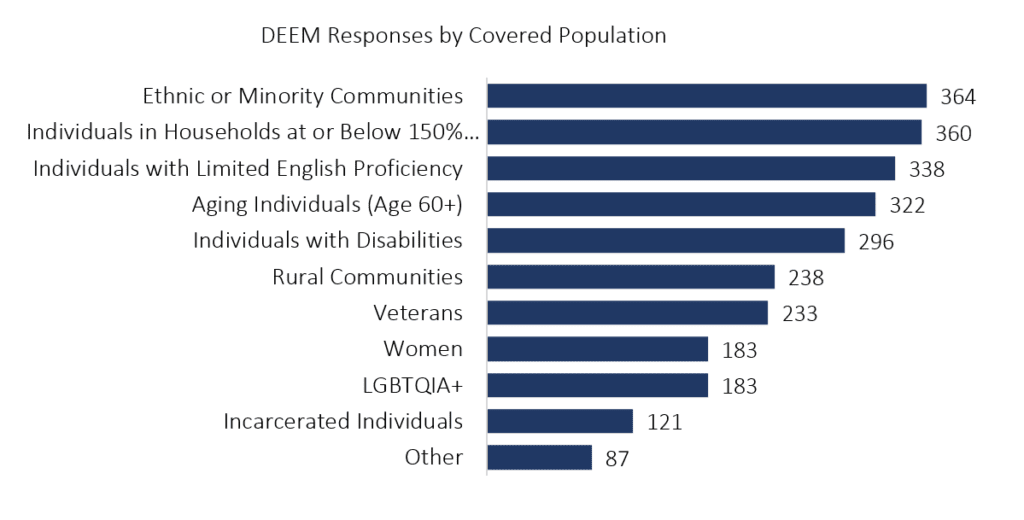

The DEEM tool indicates that there are 330 or more organizations that serve half of the covered populations, and that ethnic or minority communities are the most served covered population among the data collected. There is a stark difference between the most and least-served covered populations – for example, incarcerated individuals have access to only a third of the organizational resources that are available to ethnic and minority communities.

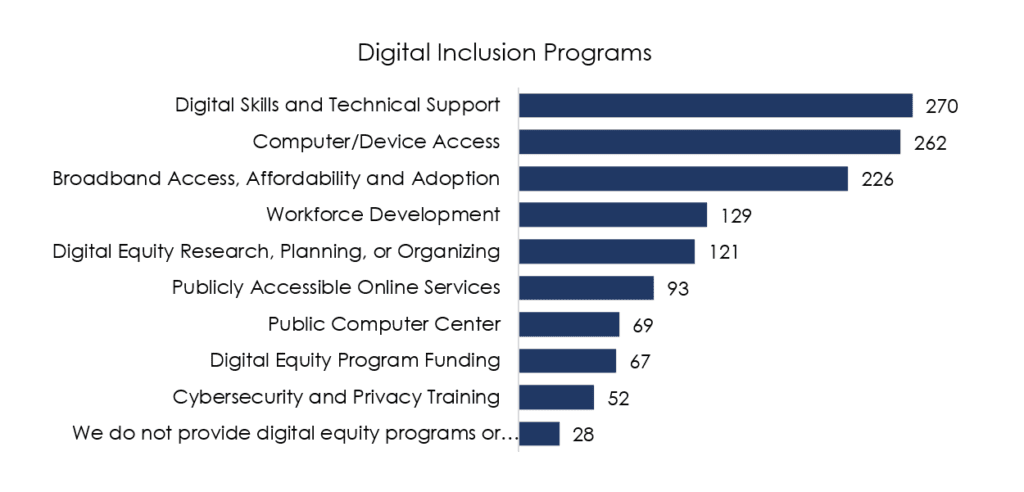

Additional Assets by Program Type

The DEEM tool collected information regarding the type of digital inclusion programs available in the State. The following chart provides a snapshot of the number of locally based programs for which CDT has collected detailed programmatic information through DEEM.

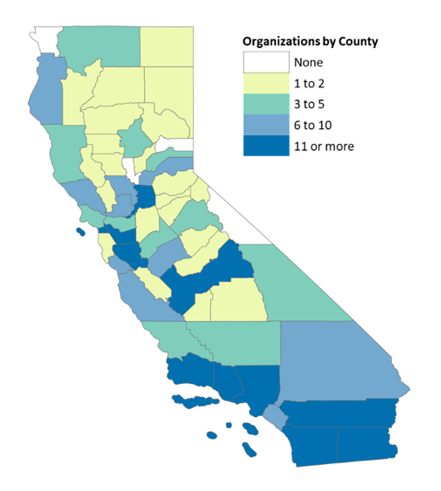

Additional Assets by County

The following chart provides a snapshot of where local digital inclusion organizations are based in the state. Given that these data is incomplete, this map represents a summary of where organizations who participated in DEEM to date are located.

It also represents the location of those organizations and may not be reflective of the service areas for each organization.

| Number of Responses | California County |

|---|---|

| None | Del Norte, Mono, Sierra, Sutter |

| 1-2 | Alpine, El Dorado, Glenn, Madera, Napa, Plumas, San Benito, San Mateo, Tulare, Amador, Calaveras, Colusa, Kings, Lake, Lassen, Mariposa, Modoc, San Joaquin, Shasta, Tehama, Trinity, Yuba |

| 3-5 | Butte, Marin, Mendocino, Nevada, San Luis Obispo, Contra Costa, Stanislaus, Inyo, Kern, Siskiyou, Tuolumne |

| 6-10 | Merced, Monterey, San Bernardino, Solano, Humboldt, Yolo, Orange, Placer, Santa Cruz, Sonoma |

| 11 or More | Los Angeles, San Francisco, Sacramento, Alameda, San Diego, Fresno, Santa Clara, Ventura, Riverside, Santa Barbara, Imperial |

Internet Service Provider Low-Cost Offers and ACP Participation

The DEEM tool also looked specifically at ISP, and asked whether they participate in ACP or offer a low-cost offer. Of the 35 entities to either participate in the DEEM tool or be listed in the BEAD Five-Year Action Plan, 18 participate in the ACP, and 17 have a low-cost offer. The complete list can be found in Appendix K.

Key Findings and Gaps in Existing Efforts

For many years, California has been the leader in digital equity. The State leads in building broadband infrastructure, connecting households to internet service, and ensuring its residents can fully utilize the technology. There are hundreds of organizations actively working to promote digital equity, which is unique to this state.

However, with all the successes the State has experienced, there are still ways to improve. Upon review of the DEEM tool responses and organizational engagement, four main barriers and gaps in existing efforts became evident. These gaps negatively impact the ability of organizations to deliver digital equity programs and services.

Top Barriers for Organizations

- Funding and Sustainability: The most cited barrier to providing digital equity services was the lack of access to sustainable funding to support their organization. Approximately two-thirds of device access and digital skills organizations reported this as their number one barrier.[24] Sustainable and reliable funding is critical to organizations providing support to covered populations across the state. This Plan intends to provide financial support to entities that provide digital equity and digital inclusion services to residents of California.

- Staff and Organizational Capacity: Adequately trained staff and support are crucial to organizations providing digital equity services. Staff are the ones out in the communities teaching digital literacy skills, conducting ACP outreach, and engaging with community members, especially members of covered populations. Solutions aimed at filling the gap in staffing and organizational capacity are addressed in this Plan.

- Difficulty Accessing and Applying for Funding: When opportunities for funding do arrive, the complexity of applying for and reporting on the funds can overwhelm organizations, especially those with limited resources. Providing technical assistance for organizations seeking grants and/or sources of government funding is addressed in this Plan.

- Lack of Awareness and Engagement: The role of community engagement in promoting digital equity supports and services cannot be stressed enough. Currently, there is a lack of awareness and engagement in communities on the issue of digital equity. Key activities in this Plan aim to support organizations doing this work.

- Coordination and Collaboration: Stronger coordination and collaboration among organizations offering digital equity resources could reduce unnecessary duplication of efforts and promote sharing resources and best practices.

Filling these gaps will be critical to the success of this Plan. By ensuring that organizations that serve covered populations and residents throughout the state have access to sustainable funding, the staff and organizational capacity to serve their communities, technical assistance in applying for and accessing funds, and support in promoting their services, we can ensure progress toward digital equity is being made.

3.3 Overview of Digital Equity Needs and Barriers

CDT developed a multi-pronged, inclusive approach to gather substantial qualitative and quantitative data to serve as this needs assessment’s baseline. The statewide telephone survey (see Appendix P), the online public survey (see Appendix S), and other data sources, such as the 2021 American Community Survey (ACS) data tables and NTIA Digital Equity Population Viewer, provide quantitative data. The Outcome Area Working Groups, Regional Planning Workshops, Tribal Consultations, one-on-one meetings, interviews, and listening sessions form the basis for the qualitative data provided in this document.

These data sources provide the baselines for the specific objectives provided in Section 2.5. The overarching objectives are:

Through this comprehensive process, the State identified common barriers to digital equity for all Californians impacted by the digital divide and specific barriers experienced by covered populations and digitally disadvantaged communities. This data builds upon the Broadband for All Action Plan, which identified access, affordability, and adoption as the top common barriers to digital equity. These overarching barriers remain today and further elucidate the findings in this Plan.

Access

Barriers to equitable access to broadband include:

- Lack of available infrastructure and service,

- Lack of reliable/resilient service,

- Evolving state broadband data and maps, and

- Uncertain localized labor supply for broadband infrastructure jobs.

A central barrier to internet access is the lack of available broadband infrastructure and service. For many California residents, businesses, and community anchor institutions, a high-speed internet connection is simply not available at their address. This barrier affects communities across the state. Many steps are being taken through the MMBI and CPUC’s last-mile programs, and efforts to increase access will be further supported by BEAD investments.

About a third of telephone survey respondents and online survey respondents who cannot access internet from home cited that a lack of available or adequate internet services at their home presented as an important barrier that contributed to their lack of home internet access.[25] According to the telephone survey, covered households, individuals with a language barrier, individuals who are members of a racial or ethnic minority group, and individuals that primarily reside in a rural area reported lower rates of connectivity at home compared to the state as a whole.[26]

Even when an address is technically serviceable by an ISP, many Californians face a secondary barrier in the lack of reliable and resilient service, as reflected by inconsistent broadband speeds and regular outages. Covered households, individuals with disabilities, individuals with a language barrier, individuals who are members of a racial or ethnic minority group, individuals who primarily reside in a rural area, and individuals who identify as LGBTQIA+ all report unreliable service at a higher rate than overall respondents.[27]

Rural communities, tribal lands, and certain urban areas face resiliency challenges that impact residents’ ability to receive online government services, conduct remote work, engage in distance learning, or benefit from online healthcare services. Lack of reliable service in rural communities hinders the effective implementation of emergency services, including delivering emergency evacuation orders to residents and locating residents who need emergency assistance.[28] The Sonoma County Broadband Strategic Plan further highlights the rural challenge, stating “rural communities are a

classic example of potentially expensive locations to build given the small number of

homes per square mile.”[29]

Californians’ need for high-performance broadband continues to increase, yet the economics of infrastructure deployment often discourage investment in rural and tribal communities.[30]Deployment in these communities often means thinner profit margins and more capital-intensive investments, which discourage competition among providers.[31]

Public interventions in the form of capital subsidies like those offered through CASF are necessary to incentivize providers to deliver service to these communities.[32] The State’s Broadband for All investments, including middle- and last-mile programs funded in SB 156, Federal Funding Account, Loan Loss Reserve Fund, and the BEAD program will further address incentives network build-out.

A third barrier associated with internet access stems from California’s state data and maps. While federal and State data and mapping capabilities continue to increase, current data and mapping definitions may not always reflect the lived experiences of communities across the state.

The CPUC has compiled extensive data within its Annual Affordability Report,[33] which aggregates pricing and service offering data from communication service providers to monitor pricing trends in different areas of the state. Continued collection of granular broadband deployment and subscriber data will allow for better understanding and assessment of unserved and underserved locations in California to effectively target resources as needed. The data will also inform public policies looking to bridge the digital divide in California.

Finally, the uncertain localized labor supply for broadband infrastructure jobs is projected to be a significant barrier to the speedy deployment of new and improved broadband networks across the state. Communities and ISPs that are poised to address the access barrier may increasingly encounter labor force challenges when they begin to build those broadband networks.

Many experts have reported that the lack of labor access is prohibitive to broadband deployment, and that long-term wage stagnation in the telecommunications industry has impeded hiring and retaining skilled workers.[34] CDT plans to collaborate closely with the CPUC to promote workforce development efforts and encourage the equitable hiring and training of employees as part of SDEP and BEAD-funded projects.

The results of this needs assessment confirm that expanding access to reliable, high-speed broadband, both at home and throughout the community, and ensuring that broadband services are adequate for the needs of households is a priority in advancing digital equity.

Affordability

In addition to access, affordability remains a top barrier for households and individuals accessing at-home broadband services. Through the engagement process, CDT identified affordability barriers that include:

- Lack of awareness of low-cost offers, such as the ACP,

- Challenging enrollment process with the ACP, and eligibility does not reflect high-cost communities within California,

- Need for a sustainable, low-cost subsidy,

- Lack of consumer choice and competition, and

- Mistrust of government and corporations.

There is a lack of awareness of low-cost offers, such as the ACP. California has invested in ongoing efforts to spread awareness of affordability programs, such as Get Connected! California Mobilization to increase enrollment in the ACP. However, as of February 2024, about 2.9 million households in California have enrolled in ACP, which represents about 50% of eligible households.[35] Nearly 77% of respondents to the telephone survey from unconnected households[36] were unaware of the program. Of those who were aware of the program but were not signed up, about 29% of telephone survey respondents stated that they thought they would not qualify, and about 23% reported not knowing how to apply.[37]

Even when households are aware of low-cost offers, the complexity of the ACP enrollment process can be challenging, and eligibility does not reflect high-cost communities within California. It is clear that “awareness is not enough to effectively increase enrollment among eligible households, and that local outreach efforts … include assistance in navigating the enrollment process.”[38] Outreach efforts must be targeted and appropriate to the different characteristics of the population across regions.

There is a continued need for a sustainable, low-cost subsidies and affordability programs, given the uncertain nature of ACP. Campaigns to raise awareness of low-cost offers and subsidies and efforts to provide enrollment assistance in these programs could be funded by the State’s allocation of the Digital Equity Capacity Grant, Digital Equity Competitive Grants, and other efforts funded by private sector and philanthropic organizations.

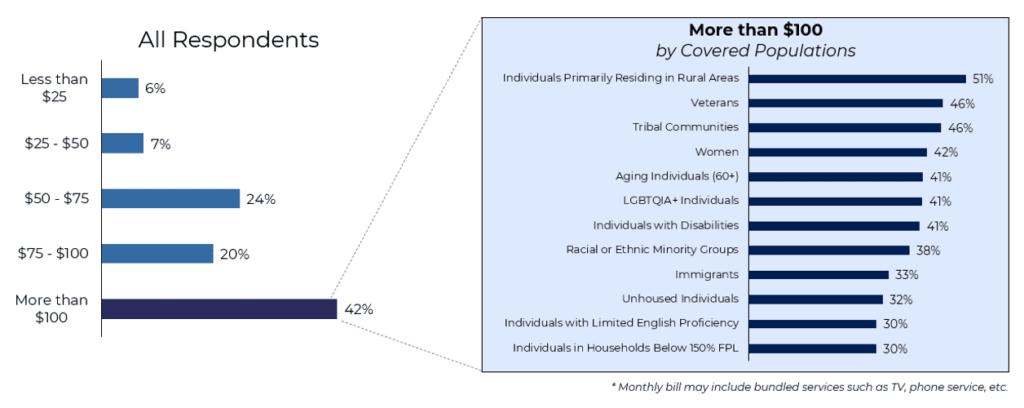

Additionally, a lack of competition amongst providers limit consumer choice and negatively impact costs for Californians. Covered population households that responded to the telephone survey cited an average monthly cost of $83.60,[39] which is comparable to the 2023 FCC Broadband Rate Survey for California of $82.40/month.[40] Online public survey respondents who can access internet from home reported paying an average of $102.72 for their home internet service.[41] Moreover, CPUC’s 2018 Competition Report found that 35% of California households have access to only one provider offering service greater than 25/3 Mbps, and only 6.8% have access to three providers offering service greater than 25/3 Mbps.[42]

The CPUC’s Rulemaking to Establish a Framework and Processes for Assessing the Affordability of Utility Service (R.18-07-006) emphasizes the importance of affordable utility services, including communications services, for individuals’ health, safety, and participation in society.[43]

Finally, we learned from the OAWGs, regional workshops, interviews, and listening sessions that another reason for households not enrolling in ACP is a mistrust of government and corporations, including a resistance among some residents to apply for programs, and a lack of information being developed in-language by trusted messengers. One respondent to our DEEM tool stated, “Many of our residents don’t qualify or won’t accept or apply for statewide services such as CalFresh, Women Infants and Children (WIC), and more. This makes qualifying or enrolling in ACP more difficult.” Existing Broadband for All investments are working to address affordability via expanding competition, including the CASF programs, MMBI, FFA, and the Loan-Loss Reserve.

Adoption

Californians face additional barriers related to digital literacy and skills, device access, cybersecurity and online privacy. These adoption barriers include:

- Lack of awareness of low-cost offers and subsidies,

- Lack of access to affordable devices,

- Lack of perceived need through a reliance/dependence on mobile phones,

- Lack of digital literacy skills and training (basic, intermediate, and advanced), and

- Lack of technical familiarity or awareness due to the rapid pace of change in hardware and software technology.

As mentioned above, lack of awareness of low-cost offers, is a barrier for households. Additionally, the cost of devices is a very real barrier to sustainable broadband adoption. Thirty-three percent of respondents to the telephone survey stated, “Nobody in my household has a desktop, laptop, or tablet computer” as a reason for not having internet access at home.[44] Ensuring households have access to high-quality, low-cost devices is important to achieving digital equity.

Among online public survey respondents, a smartphone is the most abundantly available and widely used device, with 43% of unhoused individuals relying exclusively on smartphones to access the internet.[45] For individuals with limited English proficiency and individuals in households below 150% of FPL, 23% of respondents use smartphones only.[46] Without affordable laptop or desktop computers, these individuals are highly constrained in the resources and digital opportunities they can access online.

For some, the reason they rely on smartphones and may not have a home broadband subscription is because there is a lack of distinction between cellular and broadband connection. As the Broadband for All Action Plan discusses, broadband adoption requires more than availability and affordability of service and devices. Individuals must be exposed early and often to the breadth of digital opportunities available online, including digital skills training for job opportunities.[47]

A fourth barrier to adoption is the lack of digital skills, which the telephone survey found to be the most relevant barriers for digital equity.[48] The survey distinguishes between basic, intermediate, and advanced digital skills – “basic” skills include the ability to

connect to a Wi-Fi network, send an email with an attachment, or search for

information online; “intermediate” skills include the ability to download and install a

new app on a smartphone or tablet, make an appointment online, or pay bills; and

“advanced” skills include the ability to set up protection against phishing and spam

email, set up parental controls, or delete cookies on a web browser.

The share of advanced-skills users is significantly below-average for non-English language households (40%), among low-income residents (42%), and households with disabilities (43%).[49] About a third of online public survey respondents said that they would be interested in participating in computer training classes, indicating significant demand in the state for increased opportunities for building computer skills.[50] Individuals with limited English proficiency and immigrants demonstrated the greatest interest in such opportunities.[51]

About a quarter of all online public survey respondents said they were unfamiliar with cybersecurity measures. Individuals with limited English proficiency, immigrants, individuals living in covered households, and those who identified as belonging to racial or ethnic minority groups all had lower rates of familiarity with these measures than the overall survey respondents. Veterans and rural residents had the highest rates of familiarity.[52] Cybersecurity and online privacy should be considered critical components of any digital skills training.

As technology rapidly evolves, the lack of technical familiarity or awareness of hardware and software will be an increasingly challenging barrier to address. Continued investment in digital skills training will be necessary to ensure that Californians are not left further behind, particularly for covered populations with additional vulnerabilities. An example of a program doing this work is the Santa Monica Summer Youth Tech Program that teaches “students lean start up methods, coding, leadership, critical thinking, and collaboration skills.”[53]

These barriers to access, affordability, and adoption are found across almost all covered populations and throughout the state. The implementation strategies and key activities (see Section 5) aim to address them in the State’s effort to advance digital equity.

3.4 Specific Barriers and Baseline for Covered Populations and Digitally Disadvantaged Communities

Solutions for digital equity are not one-size-fits-all, and different covered populations start from different baselines, with some in greater need than others across different dimensions of access, affordability, and adoption. This section highlights some of those differences between each covered population and digitally disadvantaged community. It includes both specific barriers that were elevated through CDT’s multi-pronged research and engagement program, as well as specific data points regarding the different baseline conditions for these populations when the baseline data demonstrates that that population needs greater attention to realize the State’s targets for a given objective.

Individuals who Live in Covered Households (under 150% FPL)

| Covered Population | Specific Barriers |

| Individuals who Live in Covered Households (under 150% FPL) |

|

Among lower-income online public survey respondents who were completely unconnected, 77% of respondents cited the Internet being too expensive as a reason by they do not subscribe to home internet, and 21% cited the lack of internet availability as the reason why they do not subscribe to home internet access.[54]

Further, there are barriers specific to multi-dwelling units (MDUs), including public housing; access to MDUs and public housing buildings poses a barrier to internet connectivity. In addition, MDUs pose a data challenge, as individual units within these buildings are often inaccurately accounted for in state and federal broadband mapping efforts.

These inaccuracies can result in a lack of eligibility for funding opportunities and can make it more difficult to target solutions. Another challenge related to housing is industry practices that constrain service availability or options where multiple families reside in the same unit.

Goal 1

All Californians have high-performance broadband available at home, schools, libraries, and businesses.

- Objective 1.1 – Increase the percentage of Californians who are connected to broadband internet service.

- Baseline – According to a representative sample of Californians surveyed for this Plan, 87% of covered households indicate they are connected, as compared to 91% of all Californians.[55]

- Objective 1.3 – Increase the percentage of Californians who report that their internet service is reliable.

- Baseline – While 62% of telephone survey respondents rate the reliability of their service at “4” or “5” (highest possible), only 58% of low-income households do so, likely because these households have fewer service options and are often priced out of higher-speed service tiers.[56]

Goal 2

All Californians have access to affordable broadband and necessary devices.

- Objective 2.1 – Decrease the percentage of Californians who cite cost as the primary barrier to internet service.

- Baseline – Seventy-seven percent of covered household respondents to the online public survey cited cost as the main reason for not having an internet connection at home, 7% higher than overall respondents.

- Objective 2.2 – Reduce the percentage of Californians who rely solely on a smartphone to use the internet.

- Baseline – Twenty-three percent of respondents from covered households use a smartphone only to access the internet, compared to 10% of overall respondents.[57]

Goal 3

All Californians can access training and support to enable digital inclusion.

- Objective 3.1 – Increase the availability of digital literacy, cybersecurity, and skills training programs.

- Baseline – CDT is tracking 270 programs that currently offer digital training skills support in the state, with meaningful differences by geography. 47% of covered household online survey respondents indicated an interest in internet or computer training class, 14% greater than overall respondents.[58]

- Objective 3.2 – Increase the percentage of Californians who have access to technical support services for internet-connected devices.

- Baseline – Twenty-eight percent of covered household respondents indicated they do not have access to technical support services in their household or community, 6% higher than overall respondents.[59]

- Objective 3.3 – Reduce the percentage of Californians whose concerns for privacy and cybersecurity prevents broadband adoption or effective use

- Baseline – Forty percent of online survey respondents from covered households are unfamiliar with cybersecurity, 18% higher than overall respondents; 31% have no cybersecurity measures setup on their devices or do not know if they do, 14% greater than overall respondents.[60]

- Objective 3.4 – Increase the percentage of Californians who possess basic, intermediate, and advanced digital literacy skills.

- Baseline – Forty-seven percent of individuals from covered households are interested in internet or computer training classes, 14% higher than overall respondents.[61] Twenty-nine percent of online survey respondents from covered households are less than comfortable with downloading and installing a new app on their smartphone or tablet, compared to 19% overall; 29% are less than comfortable making an appointment online (ex. DMV), compared to 17% overall; and 25% are less than comfortable when paying bills online, compared to 15% overall.[62] While 56% of telephone survey respondents were found to have advanced digital skills, just 42% of those in covered households reported the same.[63]

- Objective 3.6 – Increase the percentage of Californians who utilize the internet to apply for or use public benefits and other essential services and can participate in civic and social engagement online.

- Baseline – While 46% of all telephone survey respondents use telehealth, 42% of those in covered households report the same.[64]

Aging Individuals (60+ Years)

| Covered Population | Specific Barriers |

| Aging Individuals (60+) |

|

CDT worked closely in conjunction with other statewide and regional entities including California Department of Aging (CDA), AARP of California, San Francisco Tech Council, Bay Area Digital Equity Coalition, Community Tech Network and the Older Adults Technology Services (OATS) to best understand the unique barriers facing aging individuals.

Aging individuals face several barriers to digital equity, including a lack of perceived need and a lack of adequate devices and technology. They also need services, devices, outreach, training, and support to be offered in-language.[65] In addition, aging individuals often lack the digital skills and training opportunities needed to use technology such as Artificial Intelligence.

Aging individuals expressed fear of being scammed or taken advantage of when getting online.[66] When compared to the overall online public survey population, a greater share of aging individuals—more than one in four respondents who identified as aging— felt less than comfortable when connecting a computer or smartphone to a Wi-Fi network.[67] The trend on the online public survey was consistent among aging individuals for other basic skills, as well, such as sending an email with an attached image or document or searching for information about jobs and healthcare.[68] This lack of comfort with technology can be a significant barrier to using digital resources.

Goal 2

All Californians have access to affordable broadband and necessary devices.

- Objective 2.3 – Increase the percentage of Californians enrolled in low-cost internet options and subsidies.

- Baseline – According to the telephone survey, 7% of aging individuals that have heard of the ACP are enrolled in the program, 5% lower than overall survey respondents (12%).[69]

- Objective 2.4 – Reduce the average cost that covered populations pay for internet service.

- Baseline – Telephone survey results show that Californians spend an average $83.60/month on broadband, but aging individuals spend on average $85.90/month.[70]

Goal 3

All Californians can access training and support to enable digital inclusion.

- Objective 3.1 – Increase the availability of digital literacy, cybersecurity, and skills training programs.

- Baseline – Thirty-four percent of aging individuals indicated an interest in internet or computer training courses, 1% higher than overall respondents.[71] CDT is tracking 270 programs that currently offer digital training skills support in the state, with meaningful differences by geography.

- Objective 3.2 – Increase the percentage of Californians who have access to technical support services for internet-connected devices.

- Baseline – Twenty-four percent of online survey respondents who identify as aging individuals say they do not have access to technical support services in their household or community, 2% greater than overall respondents.[72]

- Objective 3.3 – Reduce the percentage of Californians whose concerns for privacy and cybersecurity prevents broadband adoption or effective use.

- Baseline – Twenty percent of online respondents who identified as aging individuals are unfamiliar with cybersecurity, 2% greater than overall respondents.[73]

- Objective 3.4 – Increase the percentage of Californians who possess basic, intermediate, and advanced digital literacy skills.

- Baseline – Thirty-four percent of online respondents who identify as aging individuals are interested in internet or computer training classes, 1% higher than overall respondents.[74] Twenty-three percent of online survey respondents who identify as aging individuals are less than comfortable with downloading and installing a new app on their smartphone or tablet, compared to 19% overall; 19% are less than comfortable making an appointment online (ex. DMV), compared to 17% overall; and 17% are less than comfortable when paying bills online, compared to 15% overall.[75] While 56% of overall telephone survey respondents were found to have advanced digital skills, just 42% of aging individuals reported the same.[76]

Incarcerated Individuals

| Covered Population | Specific Barriers |

| Incarcerated Individuals Baseline: 0.5% |

|

CDT has been working closely with the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) and its affiliate, California Prison Industry Authority (CALPIA); the Los Angeles County Jail System (LASD), which is one of the largest jail systems in the world; Santa Clara County’s Office of Diversion & Reentry Services; NextGen Policy; Tech Exchange; Ameelio; and Second Chance to address ongoing digital equity efforts for incarcerated individuals and justice impacted adults, juveniles and parolees. CDT also collected testimonials from formerly incarcerated individuals at regional planning workshops and outcome area working group sessions. CDT was unable to collect quantitative data from the telephone survey and online public survey, given human subjects research (HSR) protocol restrictions per the NTIA grant.

Through this comprehensive process that included state agencies, local jail systems,

and nonprofits supporting justice-impacted individuals, unique barriers faced by incarcerated individuals were identified. These barriers include lack of digital skills training during incarceration, housing, and economic insecurity upon their re-entry to society, and the rapid evolution of technology that occurs while incarcerated. According to the NTIA’s Digital Equity Act Population Viewer, incarcerated individuals make up 0.5% of California’s total population. There are 199,000 incarcerated individuals living in prisons, county jails, and detention centers in California who experience these specific barriers.[77]

Through its engagements with these entities, CDT learned that during incarceration, individuals have limited access to digital tools such as video calls and have lower call quality, resulting in dropping, breaking up, and merging with other calls.[78] In addition, Individuals who have been incarcerated for an extensive amount of time have a particularly difficult time with their reentry process if they have not been exposed to the technological advances that have occurred during their time in the prison system. To address this, CDCR has partnered with CDT to contract with a vendor to enable access to technology and communications via email, and video and audio calls using tablets and kiosks for incarcerated individuals in state prisons.[79] Activities on devices are monitored for safety and security. Access to educational and rehabilitative content, as well as enhanced connectivity to families and communities via these devices, are just some of the direct benefits of the ongoing rollout of tablets throughout the State prison system. For the L.A. County Jail System, however, connectivity for the 15,000 inmates is more challenging, as buildings are old and made of concrete, and Wi-Fi access is not available, even for office staff. Internet connections are hardwired and limited, as there is no ability to install data ports in every cell. The L.A. County Jail System recently sought proposals to partner with a vendor to provide each inmate with access to Wi-Fi and tablets for reading materials, email access, and video calls.

CDCR is working to obtain a Learning Management System (LMS) for its inmates and is currently repurposing gyms and dining halls with access points to serve as classrooms since Wi-Fi access is limited throughout its prison institutions. So far, about 3,000 access points have been installed in various institutions. However, greater Wi-Fi access is required to make it more widely accessible for inmates in all 33 adult institutions. CDCR hopes to eventually make it possible for inmates to continue their education in their cells without always having to be physically present in a classroom. Furthermore, CDCR has 45 fire camps that have no internet access, and access to technology and connectivity is crucial to learning how to manage fires effectively. The lack of technology at the fire camps has made it very challenging to get teachers to these sites. Hence, CDCR sees an urgent need to implement virtual classrooms at these camps.

CALPIA, which functions under CDCR, offers a Career Technical Education (CTE) program that is one of the most effective correctional rehabilitation programs in California, with a recidivism rate of only 9.5% of CALPIA CTE participants. The CALPIA CTE program provides incarcerated individuals with valuable work and training exposure and opportunities to receive accredited certifications. The CTE program includes Computer-Aided Design (CAD) and Computer Coding, among other programs. TechExchange, which offers multilingual and multicultural digital literacy training programs, is interested in partnering with NextGen Policy to scale their digital literacy, device distribution, and internship programs across the state, to include justice-impacted individuals, to enable access to technology-based internship programs in digital literacy, cybersecurity, and coding, as pathways to employment.

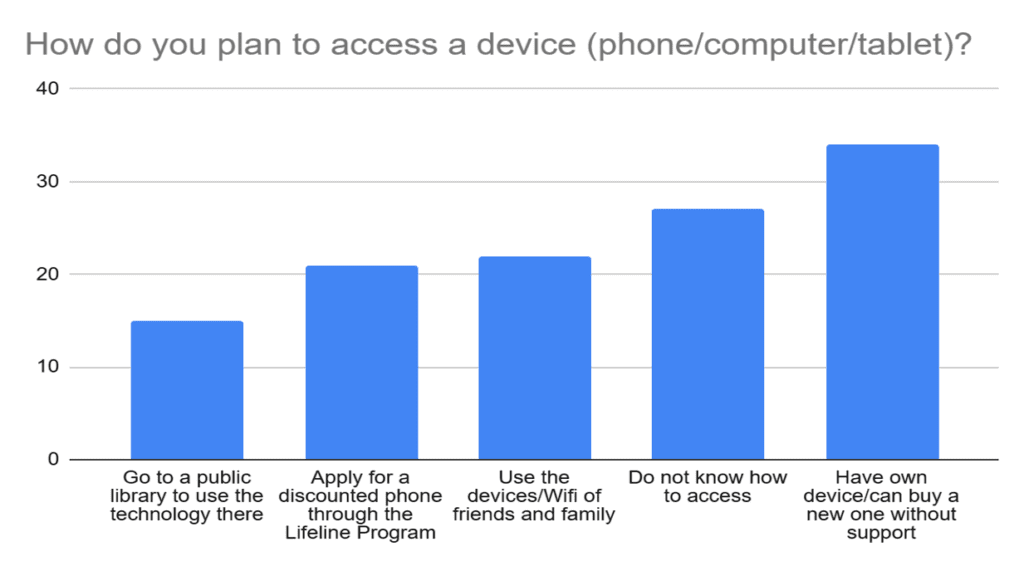

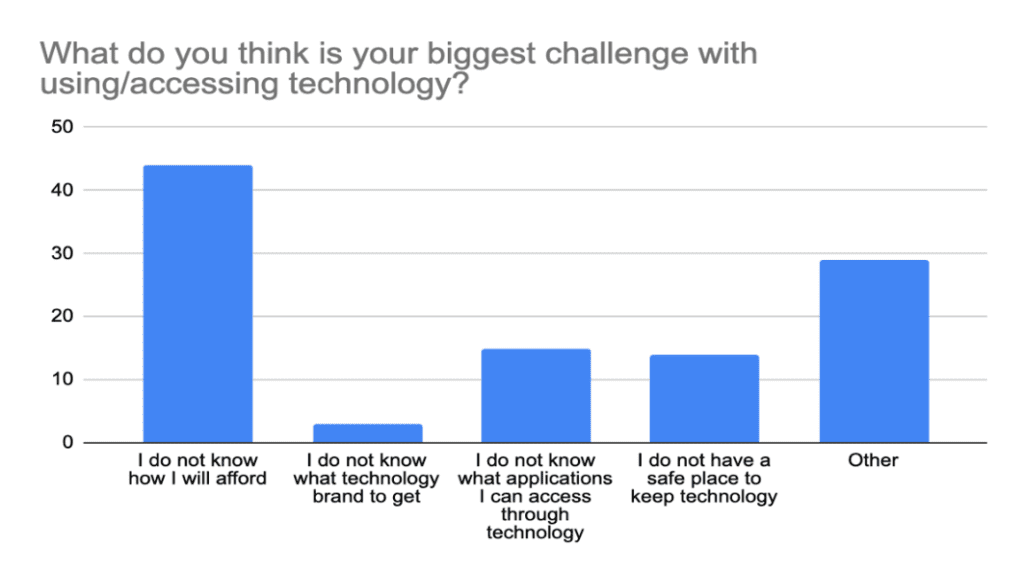

The Santa Clara County Office of Diversion and Reentry Services recently conducted a survey with assistance from Summer Fellows from Stanford University. A total of 102 surveys were administered to male and female inmates from the Elmwood Jail, partly to assess internet and device access and usage. A majority (56%) of those surveyed were between 25 and 40 years of age, and over 60% self-identified as belonging to a racial or ethnic minority. Twenty-seven percent indicated they had no income prior to incarceration, and 75% had been incarcerated for one year or less. Nearly 54% indicated they do not own any devices, 26% said they did not know how to access digital devices, and 43% reported that not knowing how to afford technology would be the biggest challenge.

CDT also learned about the importance of providing inmates with access to digital health apps to stay connected to medical and/or substance abuse treatment programs. However, there are very few digital literacy programs available for health applications.

CDT was advised that parole staff see the benefit of using technology to better manage parolees and sex offenders via pre-release video conferences and implementing overall plans for supervision that include family participation in working with parolees via technology.

Goal 1

All Californians have high-performance broadband available at home, schools, libraries, and businesses.

- Objective 1.2 – Increase the percentage of Community Anchor Institutions that are connected to broadband internet service.

- Baseline: CDCR has installed approximately 3,000 access points in various institutions. Additionally, CDCR has 45 fire camps that have no internet access.[80]

Goal 2

All Californians have access to affordable broadband and necessary devices.

- Objective 2.1 – Decrease the percentage of Californians who cite cost as the primary barrier to internet service.

- Baseline: Forty-three percent of incarcerated individuals interviewed by the Santa Clara County Office of Diversion and Reentry Services cited cost as the biggest challenge[81]

Goal 3

All Californians can access training and support to enable digital inclusion.

- Objective 3.1 – Increase the availability of digital literacy, cybersecurity, and skills training programs.

- Baseline: The baseline for incarcerated individuals is unknown; thus zero. The baseline will be established under the Capacity Grant by continuing to partner with the CDCR, local correctional facilities, entities that provide services to incarcerated individuals, and recently released individuals and families of incarcerated individuals.

Objective 1.2

Veterans

| Covered Population | Specific Barriers |

| Veterans |

|

The California Department of Technology worked closely with CalVet, American GI Forum, and several other Veterans’ organizations to identify specific barriers for Veterans.

Veterans experience unique barriers, including mistrust of government and corporations, economic and housing insecurity, and lack of digital skills and training. Additionally, Veterans are unaware of State or federal subsidy programs, such as the ACP, and how to access them.[82] Barriers expand to accessing virtual healthcare services since medical records and many health services begin by accessing the internet, and Veterans do not have the digital skills and training required.[83]

Goal 2

All Californians have access to affordable broadband and necessary devices.

- Objective 2.3 – Increase the percentage of Californians enrolled in low-cost internet options and subsidies.

- Baseline – According to the online public survey, 8% of Veterans are enrolled in the ACP, while 4% are enrolled in the Lifeline program. These enrollment rates are lower than overall online public survey respondents, which reported a 10% enrollment rate in the ACP and 5% enrollment in Lifeline.[84]

- Objective 2.4 – Reduce the average cost that covered populations pay for internet service.

- Baseline – While telephone survey results show that Californians spend an average $83.60/month on broadband, Veterans pay an average of $105.60/month.[85]

Goal 3

All Californians can access training and support to enable digital inclusion.

- Objective 3.1 – Increase the availability of digital literacy, cybersecurity, and skills training programs.

- Baseline – Twenty-nine percent of Veterans that responded to the online public survey say they would be interested in internet or computer training classes for them or their family; this is 4% lower than overall online public survey respondents (33%).[86]

- Objective 3.4 – Increase the percentage of Californians who possess basic, intermediate, and advanced digital skills.

- Baseline – While 56% of telephone survey respondents were found to have advanced digital skills, 53% of Veterans reported the same.[87]

- Objective 3.6 – Increase the percentage of Californians who utilize the internet to apply for or use public benefits and other essential services and can participate in civic and social engagement online.

- Baseline – Fifty-eight percent of Veterans that responded to the online public survey rarely or never use the internet to apply for or use public benefits ((e.g., CalFresh/SNAP, Medi-Cal, Social Security, etc.), 3% higher than online survey respondents as a whole (55%).[88]

Individuals with Disabilities

| Covered Population | Specific Barriers |

| Individuals with Disabilities |

|

CDT worked with the California Department of Rehabilitation (DOR), the California Department of Developmental Services (DDS), the San Francisco Tech Council, the Community Living Campaign, the Bay Area Digital Equity Coalition, and other organizations serving individuals with disabilities to develop survey guidance and an understanding of specific barriers to digital equity.

The recent significant increase in broadband access by individuals with disabilities “is a remarkable shift in historical trends that brings this disadvantaged group within close distance from the rest of the population.”[89] Ninety-one percent of telephone respondents who self-reported having a member in the household with a disability also cited having internet service.[90]

Individuals with disabilities experience unique barriers when it comes to digital training. A lack of access to accessible hardware and software, as well as the inaccessibility of online services, often limits those with disabilities from engaging with technology. For example, barriers noted include the lack of an inclusive digital space including top-of-the-line accessibility features for Zoom and Microsoft Teams.

In addition, there is a need for additional hardware and software training for this covered population. Compared to the overall survey respondents, a greater share of individuals with disabilities felt less than comfortable when performing basic, intermediate, and advanced digital skills. About three-quarters of respondents who identified as having a disability rarely or never use the Internet to search for available housing, compared to 63% of the overall online public survey respondents.

Goal 1

All Californians have high-performance broadband available at home, schools, libraries, and businesses.

- Objective 1.3 – Increase the percentage of Californians who report that their internet service is reliable.

- Baseline – Sixty-one percent of individuals with disabilities that responded to the telephone survey rate the reliability of their internet service a “4” or “5” (highest possible), 1% lower than what overall survey respondents reported (62%).[91]

Goal 2

All Californians have access to affordable broadband and necessary devices.

- Objective 2.1 – Decrease the percentage of Californians who cite cost as the primary barrier to internet service.

- Baseline – According to the online public survey, 76% of individuals with disabilities that do not subscribe to home internet cite the cost as a reason, 6% higher than overall survey respondents (70%).[92]

- Objective 2.2 – Reduce the percentage of Californians who rely solely on a smartphone to use the internet.

- Baseline – Twelve percent of individuals with disabilities that responded to the online public survey rely solely on a smartphone to access the internet, 2% higher than overall survey respondents (10%).[93]

- Objective 2.4 – Reduce the average cost that covered populations pay for internet service.

- Baseline – Telephone survey results show that Californians spend an average $83.60/month on broadband, but individuals with disabilities pay an average of $86.30/month.[94]

Goal 3

All Californians can access training and support to enable digital inclusion.

- Objective 3.1 – Increase the availability of digital literacy, cybersecurity, and skills training programs.

- Baseline – Twenty-six percent of individuals with disabilities that responded to the online public survey say that they do not have access to technical support in their household or community, 4% higher than overall survey respondents (22%).[95]

- Objective 3.2 – Increase the percentage of Californians who have access to technical support services for internet-connected devices.

- Baseline – Twenty-six percent of individuals with disabilities that responded to the online public survey say that they do not have access to technical support in their household or community, 4% higher than overall survey respondents (22%).[96]

- Objective 3.3 – Reduce the percentage of Californians whose concerns for privacy and cybersecurity prevents broadband adoption or effective use.

- Baseline – Twenty-five percent of individuals with disabilities that responded to the online public survey are unfamiliar with cybersecurity measures, and 19% have no cybersecurity measures set up on their devices or do not know if they do.[97] These rates are higher than those for overall online public survey respondents; 22% of whom are unfamiliar with cybersecurity, and 17% of whom have no cybersecurity measures setup on their devices or do not know if they do.

- Objective 3.4 – Increase the percentage of Californians who possess basic, intermediate, and advanced digital literacy skills.

- Baseline – Individuals with disabilities who responded to the online public survey reported higher rates of discomfort with multiple basic digital skills compared to overall survey respondents. For example, 21% of respondents with disabilities say they are less than comfortable sending an email with an attached image or document, compared to 15% of overall respondents;[98] 25% are less than comfortable with downloading and installing a new app on their smartphone or tablet, compared to 19% overall; 22% are less than comfortable making an appointment online (e.g. DMV), compared to 17% overall; and 19% are less than comfortable when paying bills online, compared to 15% overall.[99] Individuals with disabilities who responded to the online public survey also reported higher rates of discomfort with advanced digital skills, compared to overall survey respondents. For example, 43% of individuals with disabilities say they are less than comfortable deleting cookies on a web browser, while 36% of overall survey respondents say the same.[100] While 56% of telephone survey respondents were found to have advanced digital skills, just 43% of those with disabilities reported the same.[101]

- Objective 3.6 – Increase the percentage of Californians who utilize the internet to apply for or use public benefits and other essential services and can participate in civic and social engagement online.

- Baseline – Forty-one percent of individuals with disabilities who responded to the online public survey rarely or never use the internet to apply for or use public benefits (e.g., CalFresh/SNAP, Medi-Cal, Social Security, etc.), 14% lower than overall respondents to the online public survey (55%).[102]

Individuals with a language barrier, including individuals who are English learners and who have and low levels of literacy

| Covered Population | Specific Barriers |

| Individuals with a Language Barrier, including individuals who are English learners and who have and low levels of literacy |

|

CDT worked with the Central Valley Immigrant Integration Collaborative (CVIIC), the Latino Coalition for a Healthy California, Parent Institute for Quality Education (PIQE), the Canal Alliance, Mission Economic Development Agency, and Self-Help for the Elderly to better understand the barriers to digital equity facing those with language barriers, including individuals who are English learners or those who have low levels of literacy.

Individuals with a language barrier face unique challenges, especially related to the availability of information and digital skills training in an individual’s primary language. This lack of language-specific resources can make it difficult to build skills, and compared to the overall survey population, a greater share of respondents with limited English proficiency feels less than comfortable when performing basic, intermediate, and advanced digital skills.102

Workshop and outcome area working group participants raised concerns about the lack of digital skills training in their native language, and particularly, in Indigenous languages.103 In addition, a mistrust of government and corporations presents a barrier to providing resources and support that individuals are comfortable with.

Goal 1

All Californians have high-performance broadband available at home, schools, libraries, and businesses.

- Objective 1.1 – Increase the percentage of Californians who are connected to broadband internet service.

- Baseline – According to a representative sample of Californians surveyed by telephone for this Plan, 15% of individuals with a language barrier cannot connect to the internet at home, significantly higher than the 9% of overall survey respondents.[103]

- Objective 1.3 – Increase the percentage of Californians who report that their internet service is reliable.

- Baseline – While 62% of telephone survey respondents rate the reliability of their service at “4” or “5” (highest possible), only 54% of individuals with a language barrier do so.[104]

Goal 2

All Californians have access to affordable broadband and necessary devices.

- Objective 2.1 – Decrease the percentage of Californians who cite cost as the primary barrier to internet service.

- Baseline – According to the online public survey, 76% of individuals with a language barrier that do not have home internet cite cost as a reason, 6% higher than overall online survey respondents (70%).[105]

- Objective 2.2 – Reduce the percentage of Californians who rely solely on a smartphone to use the internet.

- Baseline – Twenty-three percent of individuals with a language barrier that responded to the online public survey rely solely on a smartphone to access the internet, more than double the rate of overall survey respondents (10%).[106]

- Objective 2.3 – Increase the percentage of Californians enrolled in low-cost internet options and subsidies.

- Baseline – Twenty-nine percent of individuals with a language barrier that responded to the telephone survey have heard of the ACP, lower than the overall survey respondents (32%).[107]

Goal 3

All Californians can access training and support to enable digital inclusion.

- Objective 3.1 – Increase the availability of digital literacy, cybersecurity, and skills training programs.

- Baseline – Sixty-one percent of individuals with a language barrier that responded to the online public survey say they would be interested in internet or computer training classes for them or their family, nearly double the rate of overall survey respondents (33%) and the highest proportion of any covered population.[108]

- Objective 3.2 – Increase the percentage of Californians who have access to technical support services for internet-connected devices.

- Baseline – Twenty-three percent of individuals with a language barrier that responded to the online public survey say they do not have access to technical support in Their household or community, 1% higher than overall online public survey respondents (22%).[109]

- Objective 3.3 – Reduce the percentage of Californians whose concerns for privacy and cybersecurity prevents broadband adoption or effective use.

- Baseline – Fifty-four percent of individuals with a language barrier that responded to the online public survey are not familiar with cybersecurity measures, and 33% have no cybersecurity measures set up on their devices or do not know if they do. These rates are significantly higher than overall public survey respondents, 22% of which are unfamiliar with cybersecurity, and 17% of which have no cybersecurity measures setup on their devices or do not know if they do.[110]

- Objective 3.4 – Increase the percentage of Californians who possess basic, intermediate, and advanced digital literacy skills.

- Baseline – Individuals with disabilities who responded to the online public survey reported higher rates of discomfort with multiple basic digital skills compared to overall survey respondents. For example, 21% of respondents with disabilities say they are less than comfortable sending an email with an attached image or document, compared to 15% of overall respondents; 25% are less than comfortable with downloading and installing a new app on their smartphone or tablet, compared to 19% overall; 22% are less than comfortable making an appointment online (e.g. DMV), compared to 17% overall; and 19% are less than comfortable when paying bills online, compared to 15% overall. Individuals with disabilities who responded to the online public survey also reported higher rates of discomfort with advanced digital skills, compared to overall survey respondents. For example, 43% of individuals with disabilities say they are less than comfortable deleting cookies on a web browser, while 36% of overall survey respondents say the same.[111] While 56% of telephone survey respondents were found to have advanced digital skills, just 43% of those with disabilities reported the same.[112]

- Objective 3.6 – Increase the percentage of Californians who utilize the internet to apply for or use public benefits and other essential services and can participate in civic and social engagement online.

- Baseline – While 46% of all telephone survey respondents say they use telehealth, only 37% of individuals with a language barrier reported the same.[113]

Individuals who are Members of a Racial or Ethnic Minority Group

| Covered Population | Specific Barriers |

| Individuals who are Members of a Racial or Ethnic Minority Group |

|

CDT worked with many of the same organizations that serve individuals with a language barrier such as the Central Valley Immigrant Integration Collaborative (CVIIC), the Latino Coalition for a Healthy California, PIQE, the Canal Alliance, Mission Economic Development Agency, and Self-Help for the Elderly to understand better the barriers to digital equity facing individuals who are members of a racial or ethnic minority group.

A third barrier associated with internet access stems from California’s state data and maps. While federal and State data and mapping capabilities continue to increase, current data and mapping definitions may not always reflect the lived experiences of communities across the state. Another example of a unique barrier for those who are members of racial or ethnic minority groups is the availability of digital skills training resources in multiple languages. Online public survey respondents belonging to a racial or ethnic minority group demonstrated a high interest in such resources: 43% are interested in Internet or computer training classes, compared to 33% of overall respondents.109 In addition, a mistrust of government and corporations presents a barrier to providing resources and support that individuals are comfortable with.

Goal 1

All Californians have high-performance broadband available at home, schools, libraries, and businesses.

- Objective 1.1 – Increase the percentage of Californians who are connected to broadband internet service.

- Baseline – According to a representative sample of Californians surveyed by telephone for this Plan, 12% of residents who identify as Hispanic/Latino cannot connect to the Internet at home, higher than the 9% of overall respondents. However, African American residents are connected at a rate similar to the state as a whole. The gap for other racial/ethnic groups (including Asian Americans) is generally smaller, although it is worth noting that the sample size is insufficient to characterize gaps for other groups, such as Native American or Alaska Native and for Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander.[114]

- Objective 1.3 – Increase the percentage of Californians who report that their internet service is reliable.

- Baseline – Fifty-nine percent of individuals that identify as part of an ethnic or racial minority group that responded to the telephone survey rate the reliability of their internet service a “4” or “5” (highest possible), 3% points lower than what overall survey respondents reported (62%).[115]

Goal 2

All Californians have access to affordable broadband and necessary devices.

- Objective 2.1 – Decrease the percentage of Californians who cite cost as the primary barrier to internet service.

- Baseline – According to the online public survey, 75% of respondents who identify as a racial or ethnic minority cite cost as a reason for not having an internet connection at home, 5% higher than overall survey respondents (70%).[116]

- Objective 2.2 – Reduce the percentage of Californians who rely solely on a smartphone to use the internet.

- Baseline – According to the online public survey, 15% of respondents who identify as a racial or ethnic minority use only a smartphone to access the internet, 5% higher than survey respondents overall (10%).[117]

Goal 3

All Californians can access training and support to enable digital inclusion.

- Objective 3.1 – Increase the availability of digital literacy, cybersecurity, and skills training programs.

- Baseline – According to the online public survey, 33% of respondents are interested in digital skills training, and this share is much higher for respondents who identify as a racial or ethnic minority (43%).[118]

- Objective 3.3 – Reduce the percentage of Californians whose concerns for privacy and cybersecurity prevents broadband adoption or effective use.

- Baseline – Thirty-three percent of respondents who identify as a racial or ethnic minority are unfamiliar with cybersecurity; 24% have no cybersecurity measures set up on their devices, or do not know if they do. These proportions are higher than those for overall survey respondents, 22% of which are unfamiliar with cybersecurity, and 17% of which have no cybersecurity measures set up on their devices or do not know if they do.[119]

- Objective 3.4 – Increase the percentage of Californians who possess basic, intermediate, and advanced digital skills.

- Baseline – While 56% of telephone survey respondents were found to have advanced digital skills, 54% of those who identify as part of a racial or ethnic minority group reported the same.[120]

- Objective 3.6 – Increase the percentage of Californians who utilize the internet to apply for or use public benefits and other essential services and can participate in civic and social engagement online.

- Baseline – While 46% of overall telephone survey respondents use telehealth, a slightly lower percentage (43%) of those who identify as racial or ethnic minorities say the same.[121]

Individuals who Primarily Reside in a Rural Area

| Covered Population | Specific Barriers |

| Individuals who Primarily Reside in a Rural Area |

|

CDT collaborated with the Rural County Representatives of California (RCRC), broadband consortia, and tribal communities throughout California, and numerous community-based organizations and residents at rural planning workshops to understand the barriers to digital equity faced by those primarily residing in rural areas.

Residents in rural areas face unique barriers. A lack of infrastructure and lack of competition limit residents’ options. Of the online public survey respondents that primarily reside in rural areas, 48% described their Internet service at home, in terms of speed and reliability, as not adequate (compared to 31% of all respondents).[122] Participants from rural areas (inclusive of tribal community members) noted in multiple engagement scenarios that a lack of sufficient broadband infrastructure is a significant barrier.[123] As one individual put it, “Our biggest barrier is the availability of broadband, and whether that broadband is adequate.”[124]

According to Internet speed test data from the online public survey, rural residents had the greatest share of respondents with inadequate Internet speeds, with 44% of speed test respondents who lived in rural areas having inadequate download speeds below 25 Mbps (compared to 27% of overall speed test respondents).[125]

One notable finding is the interest in digital training; 26% of online public survey respondents residing in rural areas are interested in Internet or computer training classes. However, 22% of online public survey respondents residing in rural areas cannot access support with devices or the internet in their community, which is an added unique barrier.[126] In addition, the presence of wildfires and disasters coupled with distance from support resources presents a challenge.

Goal 1

All Californians have high-performance broadband available at home, schools, libraries, and businesses.

- Objective 1.1 – Increase the percentage of Californians who are connected to broadband internet service.

- Baseline – According to a representative sample of Californians surveyed by telephone for this Plan, 11% of rural residents cannot connect to the internet from home, 2% higher than respondents overall (9%).[127]

- Objective 1.3 – Increase the percentage of Californians who report that their internet service is reliable.

- Baseline – While nearly two-thirds of telephone survey respondents (about 62%) rate the reliability of their service at “4” or “5” (highest possible), this percentage is lower among those who primarily reside in a rural area (54%).[128]

Goal 2

All Californians have access to affordable broadband and necessary devices.

- Objective 2.4 – Reduce the average cost that covered populations pay for internet service.

- Baseline – Telephone survey results show that Californians spend an average $83.60/month on broadband, but individuals who primarily reside in a rural area pay $88.20/month on average.[129]

Goal 3

All Californians can access training and support to enable digital inclusion.

- Objective 3.4 – Increase the percentage of Californians who possess basic, intermediate, and advanced digital literacy skills.

- Baseline – 33% of overall online survey respondents are interested in internet or computer training classes, though just 26% of individuals primarily residing in rural areas say the same.[130] While 56% of telephone survey respondents were found to have advanced digital skills, just 51% of those primarily residing in rural areas reported the same.[131]

- Objective 3.6 – Increase the percentage of Californians who utilize the internet to apply for or use public benefits and other essential services and can participate in civic and social engagement online.

- Baseline – While 46% of overall respondents to the telephone survey use telehealth, 44% of residents primarily residing in rural areas say the same.[132]

LGBTQIA+ Community

| Digitally Disadvantaged Community | Specific Barriers |

| LGBTQIA+ Community |

|

Members of the LGBTQIA+ community noted barriers regarding a lack of safe spaces for connecting to broadband and accessing digital literary sources.[133] Another barrier is that they are underrepresented in the broadband industry and actively promoting positions to members of the LGBTQIA+ community could address that barrier.[134]

Goal 1

All Californians have high-performance broadband available at home, schools, libraries, and businesses.

- Objective 1.3 – Increase the percentage of Californians who report that their internet service is reliable.